Knowledge worker: one who works primarily with information or one who develops and uses knowledge in the workplace. (Peter Drucker – 1959)

A simple yet visionary definition which becomes all the more more relevant today as an ever increasing part of our daily activities take place in the so-called knowledge economy where goods and services can be developed, bought, sold, and in many cases even delivered over electronic networks.

While New media increases the production and distribution of knowledge, they also play a significant role in the dissemination of information, the social fluidity and the empowerment of knowledge workers.

Yet, do we fulfill our potential and are we liberated from any constraint ? The Social Network movie delivers some answers …

Splendor

In Here Comes Everybody, Clay Shirky describes the disruptive nature of the social media along two axis. First, they implement the many-to-many communication paradigm : for the first time in communication history we have media with multiple transmitters and multiple receivers.

Second, these tools have made obsolete the theory of transaction cost by 1991 Nobel prize in economics Ronald Coase : now anyone can coordinate collective and globally distributed actions to create value (technological, business, knowledge or social) for negligible cost. One no longer needs to set up an official organisation to organize such actions.

Besides, the plummeting costs of online services have made the barrier of market entry very low. Therefore, we now have a technological and business environment in which knowledge workers have all the means to manage their professional life in a completely autonomous way. This is genuine Empowerment.

In Management Challenges for the 21st Century, Peter Drucker develops his definition and describes how the knowledge worker is freed from the Marx’s theory of alienation. According to Marx, the worker is alienated because she does not own the means of production. We, knowledge workers, do own our mean of production : the knowledge. In that respect, we’re post-Marxist and are we no longer subject to that alienation.

Misery

This empowerment does not come without some drawbacks as Alain de Botton explains in his TED talk A Kinder Philosophy of Success.

It’s perhaps easier now, than ever before, to make a good living. It’s perhaps harder, than ever before, to stay calm, to be free of career anxiety (…) Never before have expectations been so high about what human being can achieve with their life span. (…) Everybody agree that meritocracy is a great thing and we should all try to make our society a meritocratic one. The problem is that if you really believe that a society where the ones that really deserve to the get to the top get to the top, you also, by implication and in a far more nasty way, believe in a society where those who deserve to get to the bottom also get to the bottom and stay there.

As an example: Derek Sivers, who created music start-up CDBaby writes in the little guide How to call attention to your music :

It used to be that, as a musician, only 10% of your career was up to you. “Getting discovered” was about all you could do. (…) As of the last few years, now 90% of your career is up to you. You have all the tools to make it happen.

The pressure is huge for knowledge workers. The objective is hyper-productivity : David Allen‘s Getting Things Done is one of our bibles. One of the principles of the Allen’s method : if you can do something in less than 2 minutes, do it right now. The problem with digital tools : almost anything can be done in less than two minutes.

The productivity is increased with the use of tools such as Twitter. Just like traders are addicted to the NASDAQ, knowledge workers is addicted to Twitter. In the digital economy, the hyperlink is the exchange agent and, therefore, the mean to create value. Since Twitter aggregates these links, it has somehow become the stock market of the knowledge economy.

Being disconnected is not an option. It would be identified as a betrayal of the promise of fulfilment, a resignation : we are terrorized by the fear of missing out some opportunities or key data. Mark Fidelman conceded on his stream that when he sees a connected device, he tends to be nervous and does not enjoy as much his relaxing time with the family. An issue already addressed by hypertetxual.

Beyond addiction, this capacity has a psychological cost defined by Soren Kierkegaard : Angst. According to the Danish philosopher, we struggle to make sense out of our existence because we realise that our future is not determined but freely chosen.

The Social Network

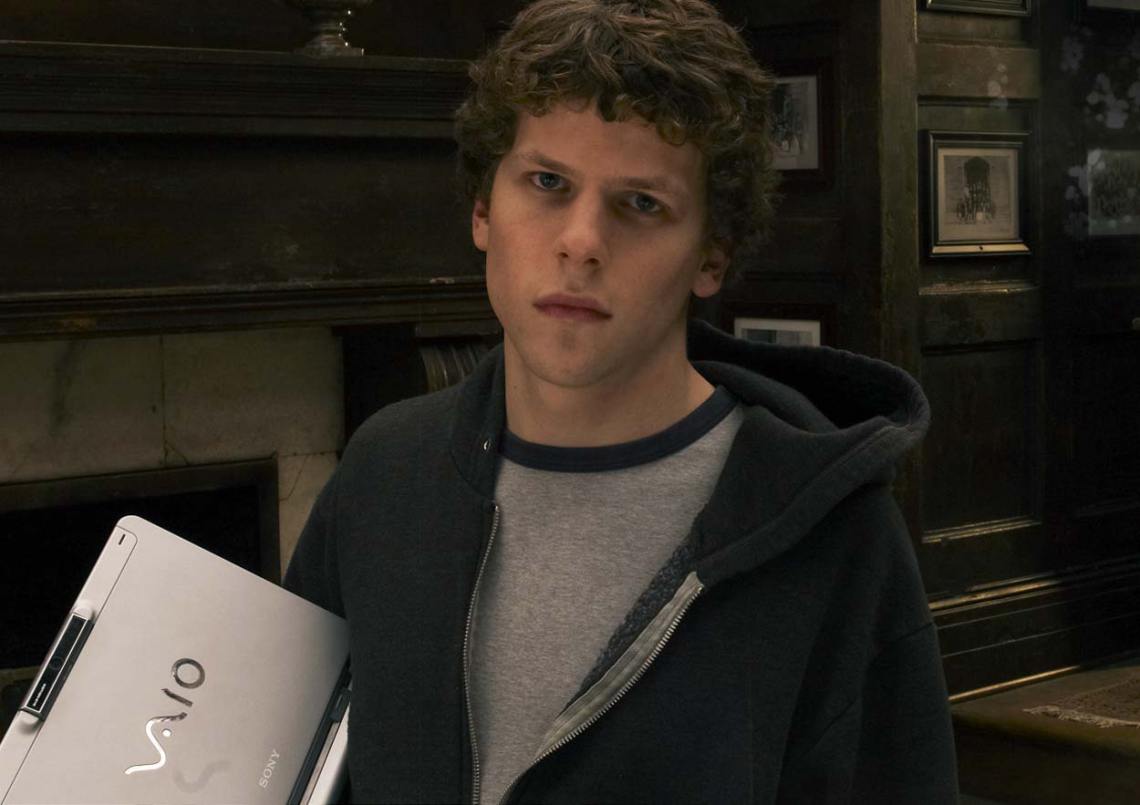

Empowerment and alienation : David Fincher‘s movie is a great illustration of these two facets.

It has never been as accessible to anyone to implement an idea as an online service and deploy it on a global scale. This is the mission of Zuckerberg with Facebook.

Facebook idea is not originally his but that is not the issue. As Lawrence Lessig highlights in his review, the movie is mostly the story of someone who gets obsessive about a project and does all it takes to complete it. Hence what Zuckerberg tells the Winklevos twins, owners of the original idea : “You are not the inventors of Facebook, if you were, you would have invented it”.

Read : you would have implemented it. In the online world, ideas are cheap, ie the idea contributes much less to the success of a project than the ability to deliver it and to make it viral.

What we witness in the movie is the inner necessity described by Kandinsky in the essay Concerning Spiritual Art : the irrepressible desire to achieve a compelling idea. This desire is increased tenfold by the empowerment offered by the networked age we are living in. Kandinsky’s inner necessity was fueled by the universal dimension of Art ; Zuckerberg’s is fueled by the universal dimension of the Internet technology. This is not money or power that Zuckerberg is interested in, it is the universal potential of his project.

The movie recounts the meteoric rise of the company and the success of Zuckerberg: a symbol of empowerment. But the same movie ends on the image of a lonely Zuckerberg, programming on his laptop as his lawyer left and called him an asshole because of his lack of empathy and his obsessive relationship with the digital world.

A telling scene about empowerment and alienation: the splendor and misery of the knowledge worker.